How Denise Verret ’88 became the first

African American woman to lead a major U.S. zoo.

By Omar Shamout

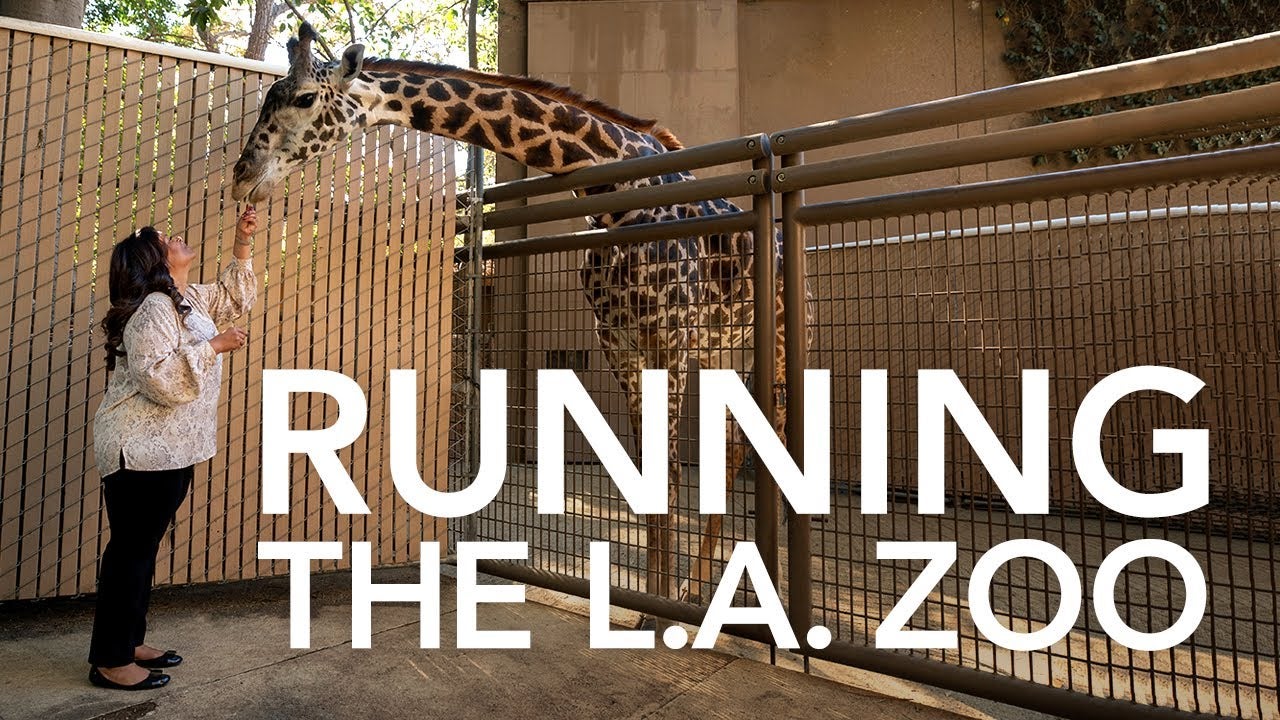

As the CEO and zoo director of the Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens, Denise Verret ’88 spends more time indoors than she would like. If she had her way, a lot more of her days would be spent with the 1,100-plus animals in the zoo’s care.

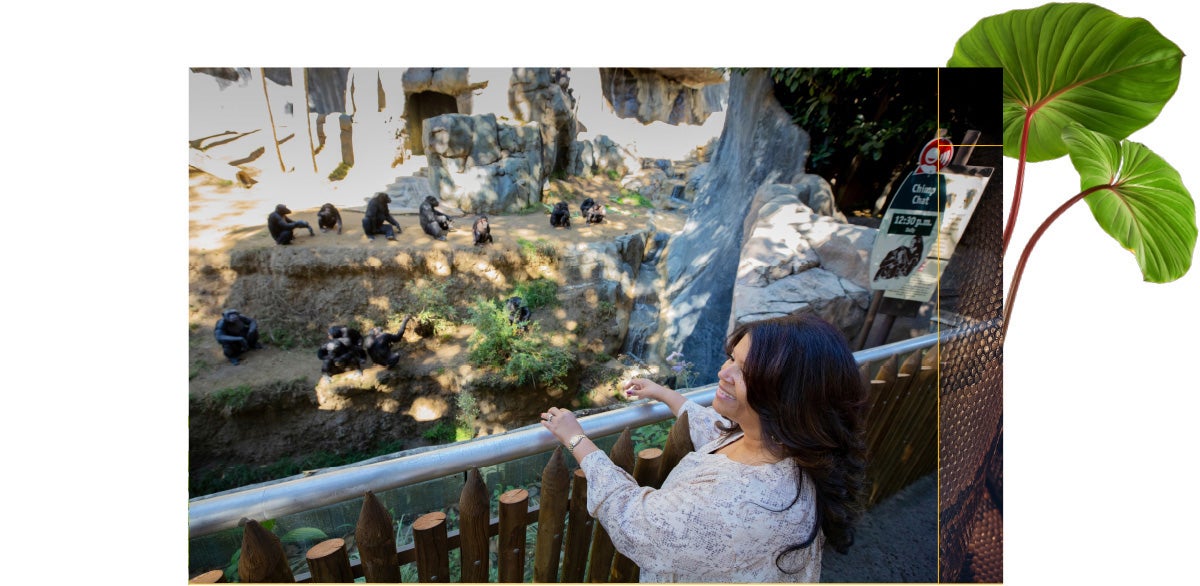

So when the opportunity arose to feed the 15 chimps gathered at the front of the zoo’s Chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains exhibit on an unusually warm November morning, the joy on her face was evident.

“I’m going to throw some more, don’t worry!” Verret, 52, called out to the assembled apes, tossing several tamarind pods over a ravine onto the rocky ledge where the animals were fighting over

the snacks.

The exhibit opened in 1998 and has been hailed by renowned primatologist Jane Goodall as one of the country’s finest chimpanzee habitats.

Earlier, in a golf cart on the way to the exhibit, Verret explained that 90% of her time is spent in meetings. She had served as deputy director of the zoo for 19 years before Mayor Eric Garcetti nominated her for the top job in June following a national search.

“During the day, most of my attention is focused on people and ways that we can make progress on organizational goals, solve problems, or discuss new ideas. Around 5 p.m., the second part of my work day begins,” Verret said, noting that’s when the office is quieter, and she finally has a chance to go over reports from the various zoo divisions, respond to emails, and get caught up on projects that require her direct attention.

Denise Verret stands in front of the L.A. Zoo’s Chimpanzees of the

Mahale Mountains exhibit, hailed by Jane Goodall as one of the

country’s finest chimpanzee habitats. (UCR/Stan Lim)

With about 230 full-time staff and another 150 or so part-time or seasonal workers, the zoo amounts to a medium-sized department in the city of Los Angeles. The City Council made the zoo an independent department in 1997; its operations had been overseen by the Department of Recreation and Parks since it opened in 1966.

But considering what Verret and zoo officials have planned for the institution’s next 30 years, it’s easy to understand why she spends so much time in meetings.

She is hoping to push forward on a “very ambitious” vision plan for the zoo that would cost nearly $700 million if fully funded and completely transform its 133-acre Griffith Park location, touching every aspect of its mission and physical campus, including animal habitats and care facilities, conservation efforts, sustainability, and visitor experiences. One noteworthy part of the plan calls for an aerial gondola to transport guests up and down the zoo’s hilly grounds.

“We hope to be able to implement a few phases before 2028, when the city of Los Angeles will host the Olympics for a historic third time,” Verret said.

By that point, the goal is to have upgrades to the zoo’s California, Africa, and/or Asia sections completed, including a California condor exhibit that would allow visitors to see the iconic birds at the L.A. Zoo for the first time.

The city’s Bureau of Engineering is preparing an environmental impact report on the plan that’s expected to be finished in July, when it would then be presented to the City Council and mayor for approval. The hope is that financing would come from a public-private partnership between the city and the nonprofit Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association, or GLAZA, which has funded exhibits, plant and animal species conservation, capital projects, and education and community outreach programs at the zoo for more than 50 years.

Road to Riverside

When Verret started her new role last summer, she became the first female African American zoo director of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums, or AZA, accredited institution in that group’s nearly 100-year history. Verret has also served as a zoo accreditation inspector for the association for the last 14 years.

“I knew the opportunity to be the first meant that I was not going to be the last,” Verret said. “It reminded me of Dr. Carolyn Murray and Dr. Maulana Karenga at UCR. That was the first time I had ever seen and got a chance to know African Americans that had Ph.D.s. I thought to myself, if they can do that, then I know I can attain whatever level in life I want to achieve in a leadership role.”

The middle child of three sisters, Denise Glascow grew up in Altadena, a sleepy Los Angeles suburb nestled at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains just north of its more famous neighbor, Pasadena. Her mom stayed at home for much of Verret’s childhood before taking a job as an accounts payable manager at Huntington Memorial Hospital. Her dad worked as a detective for the Los Angeles Police Department.

“You watch TV and police shows, and I remember thinking that’s not my dad because he was nice and kind and caring,” Verret said. “We used to have this running joke that when he would call 411 to get a phone number, by the time he finished his conversation he knew the operator’s whole life story because he could talk to anybody.”

“The whole time, I thought I was doing it until I could go back to graduate school and work in the private sector where, in my mind, the real jobs and money were. That’s what I was telling myself,” she said.

“I knew the opportunity to be the

first meant that I was not going to be the last.”

- Denise Verret on becoming the

first female African American zoo director of an AZA institution.

“As an African

American student,

it was set up for us

to thrive,”

Verret said.

A self-professed “bookworm” who joined the student government and a number of clubs at Pasadena’s John Muir High School, Verret never imagined she’d wind up where she is today. Her main exposure to wildlife came from watching NBC’s “Wild Kingdom” on Sunday nights after dinner at her grandparents’ house, where she would also read their copies of National Geographic and “take journeys” around the world through the magazine.

“I loved my pets, and my parents would take us to Yosemite, and they believed in going outdoors and on vacation,” Verret said. “But I wasn’t thinking about outdoors and animals. That just had not entered my mind.”

When it came time to apply to college, Verret knew she wanted to go somewhere that wasn’t “overwhelming in size” and also close to home. Her guidance counselor suggested UC Riverside.

She applied and got in, but Verret decided to check out the campus before making a decision. During the long drive on the 60 freeway, she recalled driving past a dairy farm full of cows and wondering what she had gotten herself into.

“I considered myself a city girl, and I’m like, where am I going?” she said, laughing. “It was a little more rural than what I was expecting.”

Undaunted, she accepted UCR’s offer and ventured east to the Inland Empire for four years. The administrative studies major said it was one of the best decisions she’s ever made.

“As an African American student, it was set up for us to thrive,” Verret said. “The intimate setting really facilitated my student success. The entire experience prepared me for entering the workforce and instilling in me the type of character that you need to be successful in life both professionally and personally.”

Verret’s favorite memory of UC Riverside is meeting her husband, Anthony Verret ’91. Denise worked in the Office of Early Academic Outreach from her sophomore to senior year, where she and others helped local underrepresented high school students make sure they were taking the right classes to apply to UC and Cal State schools.

From left: Lauren, Anthony, Brian, and Denise Verret

at Brian’s UCR graduation in June 2019. (UCR/Stan Lim)

Anthony stopped by the office one day, and Denise asked if he wanted to help stuff packets for an event that night. Anthony obliged, and Denise offered to take him to lunch as a thank you.

Anthony took her up on the offer a few weeks later — only he managed to pay before she could pull out her wallet.

“That kind of annoyed me!” she said about Anthony, who majored in human development and now works as an LAPD lieutenant.

Denise managed to forgive him, and the couple have now been married for 26 years and have two grown children — Lauren, 20, an aspiring film and TV make-up artist; and Brian, 22, who graduated from UC Riverside in 2019 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology.

“Neither my husband nor I suggested it; he selected it on his own,” Verret said about Brian’s decision to attend UCR. “I found it ironic, but not surprising, that he had the same experience that I had.”

Civil servant

Though UC Riverside set her up for success, Verret had no idea what type of career she wanted to pursue after graduation. With thoughts of an MBA swimming through her head, her aunt, who worked for the city of Los Angeles as an executive administrative assistant, asked if she might be interested in a summer job with the city.

That sounded like a good short-term option to Verret, so she interviewed with the assistant city administrative officer, who hired her on the spot. She began her career as an intern in the capital projects group for municipal facilities, which oversees infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges, and police and fire stations.

Her three-month gig turned into a year when she accepted another post with the city’s disaster preparedness group. About halfway through that internship, a colleague recommended she take the city’s employment entrance exam, so she could keep her options open. Not long after, Verret landed a full-time position.

“The whole time, I thought I was doing it until I could go back to graduate school and work in the private sector where, in my mind, the real jobs and money were. That’s what I was telling myself,” she said.

Thirty-one years later, Verret is still working for the city of L.A., albeit with a bit more responsibility than when she started.

“I liked government; I liked seeing how it worked,” she said. “I liked contributing to policy decisions that impacted people’s lives — and just never left.”

With new leadership and guidance, the zoo implemented over 530 improvements and received AZA reaccreditation. Verret was hired to serve as deputy director in May 2000.

A pair of okapi, the only known living relative of the giraffe,

which hail from the Democratic Republic of Congo. (UCR/Stan Lim)

By the mid-1990s, Verret had risen to the role of senior administrative analyst and was tasked with writing reports on the zoo, which had fallen on hard times due to chronic underfunding and an outdated infrastructure.

Partly as a result of those reports and Verret’s recommendations, the zoo was spun off from the Department of Recreation and Parks into its own City Council-controlled unit, and its first zoo director was hired. With new leadership and guidance, the zoo implemented over 530 improvements and received AZA reaccreditation. Verret was hired to serve as deputy director in May 2000.

L.A. (Zoo) story

The road to building the Los Angeles Zoo was long, winding, and like many L.A. tales, lined with celebrities, intrigue — and a media circus.

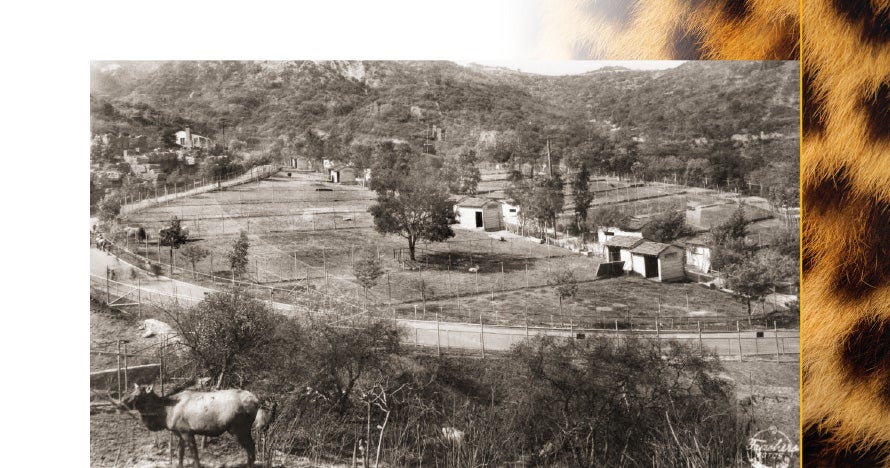

In 1913, the city built its first zoo in Griffith Park, moving animals to a small site on the eastern side of the park from a zoo in Eastlake, now Lincoln Park, which had opened in 1885. Railroad and mining tycoon Frank Murphy also donated animals from his own private zoo, including antelope, mountain lions, foxes, monkeys, peacocks, bobcats, and deer, according to historian Mike Eberts in his 1996 book, “Griffith Park: A Centennial History.”

But the new zoo ran into trouble almost immediately and was plagued by a litany of problems throughout its half century in operation thanks to a lack of investment, crude and cramped facilities, and understaffing — it didn’t even have a veterinarian when it opened.

The zoo came under attack in 1916 after the health department discovered its sewage was draining into the Los Angeles River. Also during World War I, the City Council opted to save money by feeding horse meat to the meat-eating animals rather than beef, causing many of them to die. A New Year’s Day flood in 1934 forced the zoo to temporarily turn the bears loose in the park, and the water damage took a year to clean up.

The old Griffith Park Zoo in 1939.

The Works Progress Administration delivered some much-needed improvements in 1937, but the criticism continued. Many Angelenos had also grown frustrated that their tiny zoo had been far surpassed in size and reputation by the San Diego Zoo. Three years later, voters approved a $6.6 million bond to build a brand new zoo. Unfortunately, no one could agree on where to put it or who should run it.

The City Council and nonprofit Zoological Society of Los Angeles wanted to build it in Chavez Ravine, but by December 1957 that site had already been promised to Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley as an enticement to move his team west and build a new stadium.

Mayor Norris Poulson proposed the zoo be located in Elysian Park and operated by the nonprofit now known as Friends of the Zoo and led by millionaire Wilshire Oil Co. executive Maurice Machris.

However, an outcry erupted when opponents suggested the publicly funded entity should not be turned over to a private group that would charge visitors for an attraction that had always been free.

The vociferous debate played out prominently in the press and even included an offer from Roy Rogers to operate the zoo. By 1961, public opinion had soured on Elysian Park. The mayor had begun to back a plan to put the zoo in Pacoima, while others supported an expanded Griffith Park site that would replace the Roosevelt Golf Course, even though that proposal angered golfers.

Think of it as “internet dating for zoo animals,” joked animal keeper Mark Linggi.

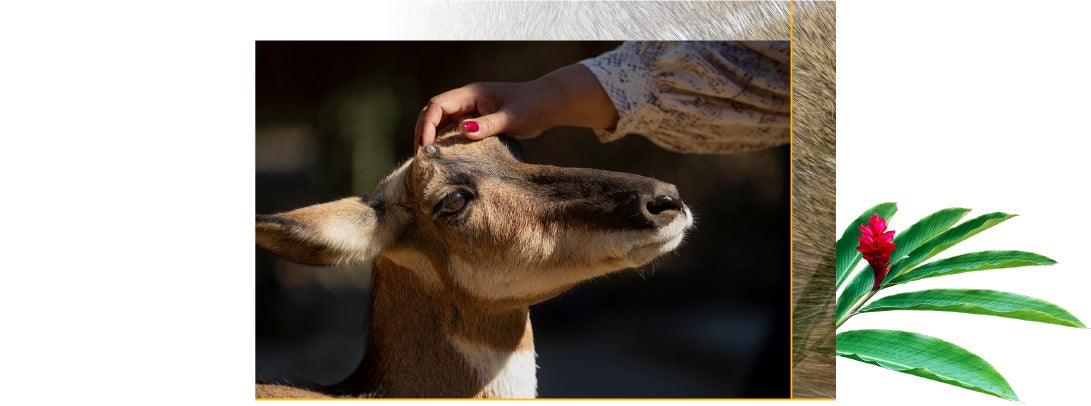

Verret pets one of the zoo’s peninsular

pronghorns, a critically endangered species

native to Baja California. (UCR/Stan Lim)

Perhaps out of exasperation, an idea was even floated to spend the bond money on a monorail to San Diego to make it easier to visit that city’s zoo.

Because newly elected Mayor Sam Yorty refused to consider Elysian Park a viable site given its steep hills, the Friends asked him in 1962 to nullify an agreement they had reached with the city three years earlier to operate the zoo.

Zoo architect Charles Luckman championed the Griffith Park proposal, helping it win approval from the Recreation and Parks Commission — five years after the bond measure’s passage — due to its central location and the low cost of building access roads from nearby freeways.

At long last, L.A. would have its big, shiny new zoo — in another four years.

Conserve and protect

Talk to any animal keeper at the L.A. Zoo for more than a minute, and you’ll likely hear the term “Species Survival Plan.” The AZA operates about 500 such plans in an effort to oversee the population management of select species within its member institutions and enhance conservation of those species in the wild.

The L.A. Zoo has a long history of helping to preserve endangered species. As an inaugural partner of the California Condor Recovery Program, which launched in 1982, the zoo has helped boost the California condor population from just 22 birds in the 1980s to nearly 500 today, more than half of which live in the wild.

Also in 1982, the zoo took in six endangered Victorian Koalas from the Melbourne Zoo, a major achievement for the institution given that even today only 10 zoos in the United States offer visitors a chance to glimpse the cuddly Australian mammals.

The zoo currently has about 50 animals whose species are governed by a Species Survival Plan, each led by a team of experts that decides which animals from which zoos should be paired off for successful breeding.

Think of it as “internet dating for zoo animals,” joked animal keeper Mark Linggi, who works with the zoo’s 10 female peninsular pronghorns, a critically endangered species native to Baja California. Capable of running 55 mph for up to an hour, pronghorns are the fastest land mammals in North America.

Other animals at the zoo whose species are governed by these plans include the aforementioned chimps, Asian elephants, gorillas, and okapi, the only known living relative of the giraffe, which hail from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The L.A. Zoo is also one of four U.S. institutions that send experts to Congo to advise staff at the Gorilla Rehabilitation and Conservation Education Center, which is dedicated to preserving Grauer’s gorillas. One of the zoo’s vets will also be traveling to Ecuador to provide veterinary expertise to a field research project on mountain tapirs, which further supports the zoo’s tapir captive breeding program. The L.A. Zoo also provides funding to a number of international wildlife conservation projects.

In the late 1990s, Los Angeles voters approved several bond measures, which together with city funds and donations raised by GLAZA, allowed the zoo to invest more than $172 million in improvements and new construction projects such as the gorilla, orangutan, and elephant exhibits; the Rainforest of the Americas experience; the Gottlieb Animal Health and Conservation Center; the Winnick Family Children’s Zoo, and the Children’s Discovery Center, among others.

On a visit to the $15 million, 50,000-square foot Gottlieb Center, which sits nestled at the top of the hill, Dr. Stephen Klause, one of four staff veterinarians, had recently finished a pair of procedures — one on a green-winged macaw named Popeye to remove tissue on the inside of his mouth; and another on Sammie, a shingleback skink that needed scar tissue removed from its left eye socket. The eye had to be removed about 20 years ago due to cancer.

An idea was even floated to spend the bond money on a monorail to San Diego to make it easier to visit that city’s zoo.

Verret admires a green-winged macaw named Popeye following his procedure

at the Gottlieb Animal Health and Conservation Center. (UCR/Stan Lim)

Zoo vets have to be prepared to treat everything “from mice to elephants,” though they can’t all fit on the same operating table, Klause noted with a chuckle.

Stellar facilities like this one helped the L.A. Zoo receive AZA accreditation, which Verret described as “the gold stamp of approval” in the field. The institution also increased the size of its staff in the 1990s and the early 2000s, allowing it to support the operations and maintenance of new exhibits, beef up community engagement efforts, expand its educational programming, and much more.

The zoo has also added more nighttime programming over the last few years, including the Brew at the L.A. Zoo event and Roaring Nights music series, both of which are aimed at millennials, and the holiday L.A. Zoo Lights experience.

“We want to drive people here of all ages and then teach them about our animals, animal programs, and conservation efforts at the same time,” Verret said, noting she hopes the vision plan will also boost tourist attendance.

The zoo, she said, represents the best of Los Angeles, a place she loves dearly and has dedicated her life to serving. And on nights and weekends, you’ll likely find the sports fanatic cheering on the Clippers or Dodgers.

“I absolutely love the things that Los Angeles represents, from culture, diversity, and progressiveness, to innovation and technology, institutions of higher learning, and phenomenal cultural centers,” Verret said. “Being the sports mecca and the entertainment capital of the world, there is so much that makes us unique and sets us apart from any other city on the planet. I just think the zoo is positioned to do things that will make us uniquely Los Angeles.”

Visit creatorstate.ucr.edu to hear Verret and other guests talk about their stories of social innovation, art, and entrepreneurship on UCR’s podcast, “The Creator State.”