Elizabeth Watkins began serving as UCR’s provost and executive vice chancellor on May 1. (UCR/Stan Lim)

UNCHARTED

UCR’s new provost loves to plan,

but her road to Riverside was unpredictable.

By John Warren

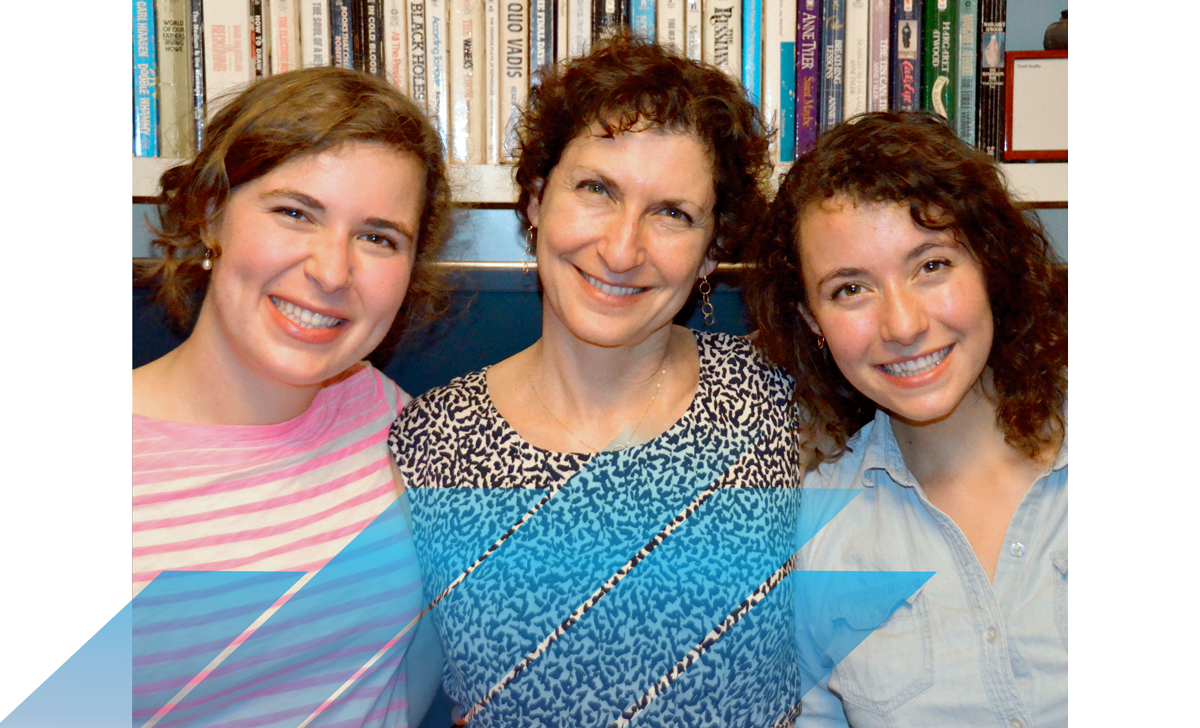

here is a joke in Elizabeth Watkins’ family that, if she had a vanity license plate, it would read “LUV2PLN.” Consider this recent episode relayed by Watkins’ two daughters. Watkins — who became UC Riverside’s provost and executive vice chancellor in May — wanted to surprise her older daughter, Emily, with a visit from younger daughter Ellen, who lives in New York City. Mom, who goes by Liz, was worried that Emily — with her in Southern California for a visit — might see the text messages on her phone after Ellen landed at LAX. So Liz devised code phrases for Ellen.

To let her mom know the plane had landed, Ellen would type: “Hi, mom. How are you?”

Liz would respond with: “Great. Teddy (her grandson) is here.”

When Ellen arrived at the rental car counter: “How long is he staying?”

Liz: “Until Sunday.”

When Ellen was five minutes away: “Great. How fun.”

It worked.

Watkins, center, with her daughters Emily, left, and Ellen in 2014.

“I was hanging out in the backyard with my baby boy, and Ellen walked out with my mom. I shrieked,” said Emily, 33, a medical doctor in Portland, Oregon. “I was so shocked. It was delightful.”

“She loves to plan, and she has a great way of thinking about how to make things better,” Emily said. And “she’s very good at turning everyday things into games,” added Ellen, 29, a high school science teacher.

A penchant for planning, along with consensus building, has been key to Watkins’ professional success. But if there’s a conventional way to become the top academic officer on a college campus, it’s not Watkins’ story. Born Elizabeth Siegel, she grew up in Warwick, Rhode Island. Her parents were both native New Yorkers. Her father, Eddie, was in the family textile business. Her mother, Judy, taught public school, then became a school psychologist, then a real estate developer.

“Classic 1960s suburbs; all the houses looked alike,” Watkins recalled. “Tennis in the summer, skiing in the winter.”

She played on Toll Gate High School’s 1979 championship tennis team in the No. 1 singles spot.

“She had a perfected and repetitive style,” said her lifelong friend and tennis teammate Leslie Hoyt. “She didn’t make a lot of mistakes.”

Hoyt remembers Watkins leading impromptu cheers on the team bus. “P-S-Y-C-H-E-D … Psyched! Let’s geeeeet psyched!”

Watkins earned her bachelor’s degree in biology from Harvard University in 1984; she would later earn her doctorate in the history of science, also from Harvard.

“She juggled so many different things from a career and mom standpoint, and she made it look realistic,” Emily said. Ellen added: “As a kid, things were very easy for us.”

A job as senior historian at a museum in Pittsburgh led to adjunct teaching at Carnegie Mellon University. Her story became one familiar to humanities scholars. Year after year, she worked as an adjunct, teaching two or three classes in American history and history of science each semester, her prospects for a full-time, tenured professorship seemingly growing dimmer. Then, finally, a full-time position came up at Carnegie Mellon in 2003.

“I wasn’t even interviewed,” Watkins said.

“She is super goal-oriented and ambitious,” Ellen said. “As a kid, you want your parents to be happy, and she wasn’t happy.”

Watkins with her husband, John Janetos, in 2017.

What came to Watkins then, at 42, must have felt like clouds — or even oceans — parting. A Hail Mary application to UC San Francisco resulted in an offer for a tenured faculty position as an associate professor of History of Health Sciences. Watkins calls the decision to apply part of her “Horatio Alger story of academia,” after the 19th century author who preached perseverance through hard work. For two years, she was a cross-country mom, building her career at UCSF and flying home to Pittsburgh every other weekend. Her research focuses on the interrelations of medicine, science, gender, commerce, and culture in the United States. An author of five books and numerous articles, she has become a leading expert on the history of birth control, sex hormones, and prescription drugs.

At UCSF, her proclivity for planning served her well. Wendy Winkler, Watkins’ chief of staff at that institution, identified a common thread in Watkins’ leadership style: Plan, build consensus, then step forward decisively. Soon, Watkins’ get-it-done attitude drew attention. When the graduate dean retired in 2012, she was asked to apply for the position, which supports 19 doctoral programs, 11 master’s programs, and more than 1,000 postdoctoral scholars.

“When I got the job, it totally came out of left field for many faculty,” Watkins said. “At UCSF, everyone who served as a dean was either a clinician or a biomedical scientist.”

A first project as dean was developing a more transparent model for allocating funding to students in the Graduate Division.

“It was Wendy and Liz on the road,” Winkler recalled, with the two hosting face-to-face meetings across campus over several months.

The measure was approved. A year later, in 2013, she was asked to become vice chancellor of student academic affairs — in addition to her role as dean. It was a massive job in itself, supervising more than 100 staff members and overseeing all student affairs functions, including the registrar and financial aid, student health and counseling services, institutional research, education technology services, career services, student life, and international students. In 2018, she spearheaded the successful 10-year accreditation for the entire university. The process took two years, into the pandemic, and involved another installment of “Wendy and Liz on the road.”

“People really like to be asked what they’re thinking; people like to be listened to. She did it, easily,” said Winkler, who retired from UCSF this summer, soon after Watkins took the UCR post. “It served her so well in that she didn’t listen to gossip or second-third hand stuff — she wanted to hear it directly.”

Winkler often heard her colleague and friend say the following: “If you disagree with me, you must tell me.”

By all accounts, Watkins had a good thing going at UCSF. But at 58, she decided to apply for UC Riverside’s vacant provost position. Her decision had much to do with UCR’s mission, serving a large population of first-generation, underrepresented, and low-income students.

“I thought, UCR is not just talking the talk, they are walking the walk on inclusive excellence,” Watkins said. “And I would like to help make a difference here.”

Daughter Emily invoked Mary Poppins to explain.

“She descends in where she’s needed,” Emily said. “And when she’s achieved what she hoped to, she moves on to the next goal.”