OFFICE HOURS

LIVING THE DREAM

Inspired by her family, Jennifer R. Nájera aims to change the conversation on immigration.

By Jessica Weber | Photos by Stan Lim

On the desk in Jennifer R. Nájera’s office sits a framed copy of a 2019 op-ed she authored for the Los Angeles Times, her first for the outlet. In it, Nájera details her family’s journey from Mexico to Texas across the Rio Grande in the 1940s, the economic issues underpinning the migrant farmworker immigration debate, and the continued struggle of undocumented “Dreamers.”

“I had the privileges of a U.S. citizen,” wrote Nájera, 45, who was born in Bakersfield. “But as the granddaughter of undocumented immigrants, I know how easily my life path could have been different.”

Nájera’s family history is at the heart of her research. Her mother was the first in her family to be born in the U.S., and her father was the last in his to be born in Mexico. Both grew up in agricultural communities and worked in the fields as teenagers. An associate professor and chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies, Nájera has spent her career studying the intersection of education and immigration.

“I’ve always felt this connection to immigrant communities,” she said. “There’s not such a great divide between those of us whose families are ‘legal’ and those of our families who are ‘illegal.’”

Nájera received a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s in education from Stanford University, followed by a doctorate in anthropology from the University of Texas where she focused on Mexican American studies. An undergraduate research project involved speaking with Mexican women who lived alone while their husbands worked in the U.S. For a master’s project, she interviewed children of immigrants to see if their views of the U.S. matched those of their parents. Nájera chose the Texas border town where her mother was raised as the field site for her doctorate, wanting to research the communities still living there. Her work evolved into her first book, “The Borderlands of Race: Mexican Segregation in a South Texas Town.” Nájera considers herself part of an effort by scholars of color to decolonize the discipline of anthropology by allowing communities to speak for themselves.

“I’ve been trying to learn from immigrants and to think through things like the American dream and assimilation,” Nájera said. “It’s not just about our own subjectivity and relationships with the community, but also being active in the community.”

Nájera’s research centers on undocumented students and how their status and that of their families affects their education. Her goal is to broaden the understanding of education and expand ideas about whose knowledge is valuable by acknowledging what students learn from their parents and communities. She said many undocumented students also bear the burden of educating others about eligibility for financial aid and clearing up misconceptions about undocumented immigrants’ effect on the economy and job market.

“One of the things I’ve learned working with undocumented students in general is that they dislike being referred to as a ‘Dreamer’ because it positions them as a good, deserving immigrant, and that means there are other immigrants who are not good and deserving — and usually those immigrants are their parents,” she said. “Part of my research is to try to open up knowledge and, hopefully, opportunity for new generations of immigrants by trying to change the discourse about the immigrant community.”

Nájera, who joined UCR in 2006, is also involved in UC PromISE, a collaborative research effort between several UC campuses, which aims to better understand the academic, financial, and mental health effects of immigration policies on undocumented and mixed-status students and provide development opportunities. Through her research and other efforts, Nájera hopes to see real immigration reform.

“Our immigration system is broken,” she said. “If we are able to persuade people, then the policymakers won’t feel as nervous about passing pro-migrant policy because they know that their constituents support it.”

1. CLAY POT FROM STUDENT

Nájera has received many souvenirs from students from all over the world. She keeps this clay pot on her desk, which a student brought back for her from Oaxaca, Mexico. “I always thought that it was really lovely that my students are traveling the world and thinking of me,” she said. “They’re part of me because of the things they’ve taught me over the years.”

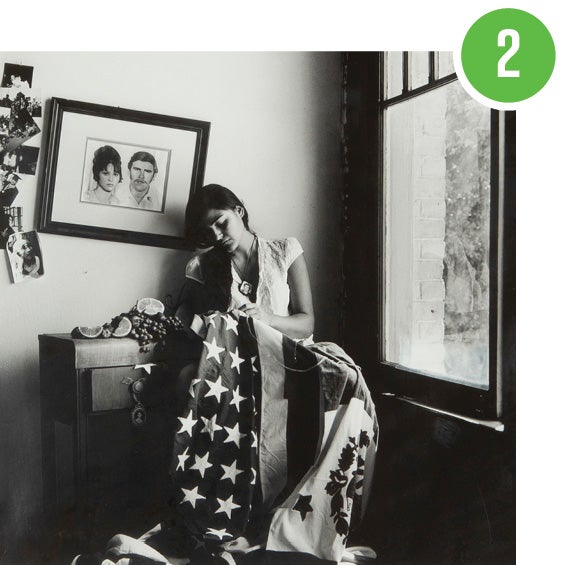

2. PHOTOGRAPH OF WOMAN AND FLAGS

Shortly after moving to Riverside, Nájera went to an exhibition featuring Chicano artists where she bought what she calls her first “real” piece of art. The black-and-white photograph, which hangs in her office, depicts a woman sewing together the American and Mexican flags. “I just thought it was really moving, thinking about how to bring these identities together,” she said.

3. CASA ZAPATA MURAL

This image depicts one of many murals on the walls of Stanford’s Casa Zapata student residence where Nájera lived as an undergraduate. In it, two guerilla fighters hide behind a wall holding calla lilies instead of rifles. “It was such a beautiful representation of the different ways we can fight for things we believe in or that are important to us,” Nájera said. “I have a lot of desires to create a world that I want my kids to grow up in — one that is humane, generous, and welcoming again. Part of the way I do that is through writing and listening to people.”

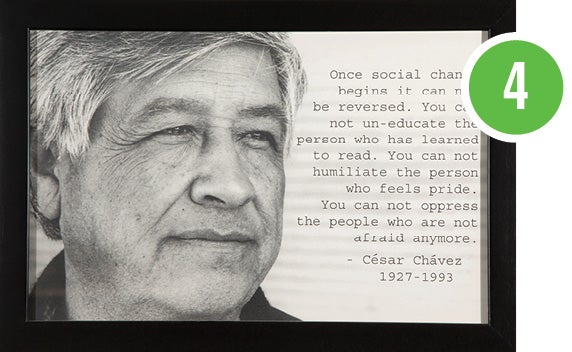

4. CESAR CHAVEZ QUOTE

Nájera said she reads this quote by Mexican American labor and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez aloud at the end of each class. She added her mother’s family was part of several protests mounted by Chavez’s Unified Farm Workers union, and her aunt and grandfather were arrested outside of a Safeway for protesting farmworker conditions. “It’s really important for me as a professor to convey to my students what they’re accomplishing with their education,” she said. “There are things it gives you that are not necessarily material.”