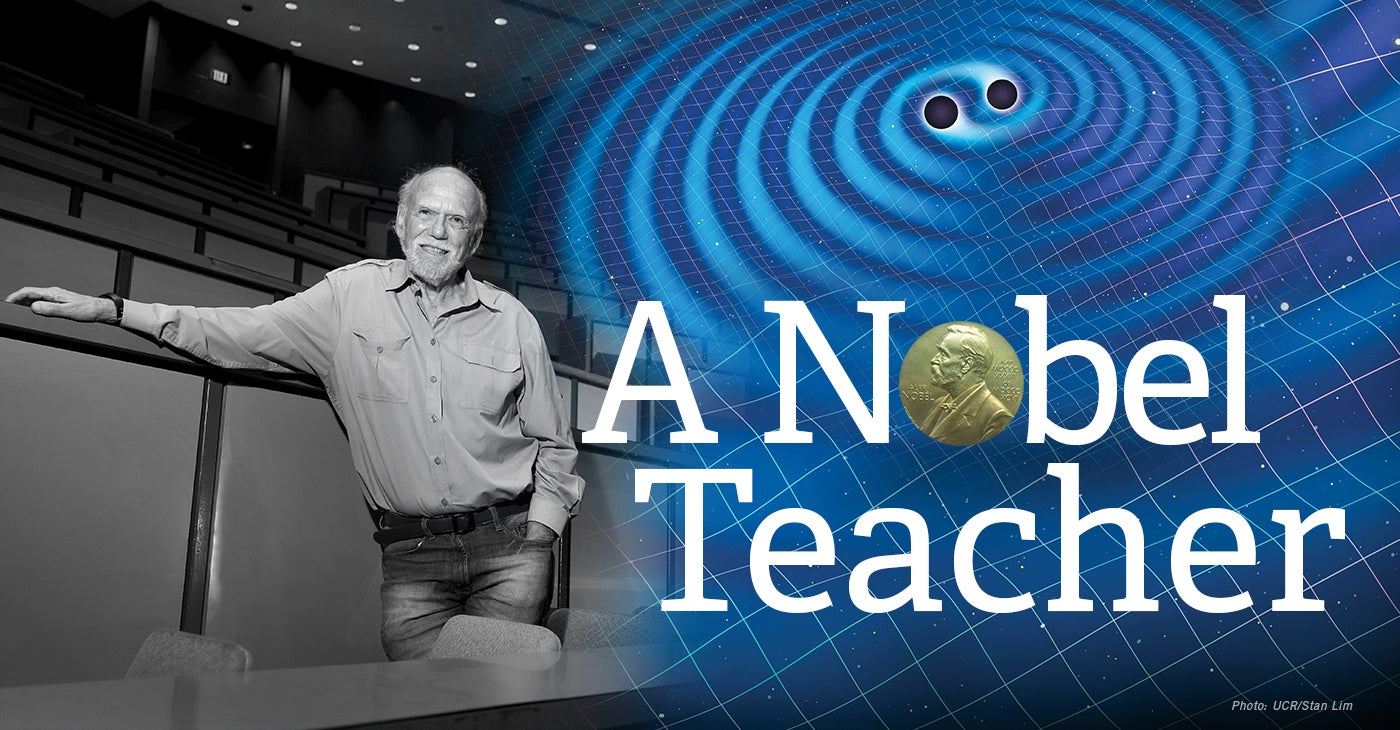

Barry Barish brings a lifetime of teaching and research to UCR students.

By Omar Shamout

On the morning of Thursday, April 11, Barry Barish picked up his copy of the New York Times and sat down to read the paper at his Santa Monica home.

Staring up at him from the front page was an image of a supermassive black hole, the first such photo ever captured — a historic scientific and technological achievement that made headlines around the world.

Barish, a distinguished professor of physics and astronomy at UC Riverside, later decided to scratch his planned lecture in the course he was teaching that quarter, Physics 224: Frontiers of Physics and Astrophysics.

“How could I be talking about the frontiers of physics and astrophysics and not lecture about that?” Barish said.

But there was a problem — he had only 24 hours to prepare. If he was going to lecture for a whole hour on the discovery, he had to understand the ins and outs of how the team of more than 200 astronomers from around the world took a photo of an astronomical object some 55 million light-years from Earth.

So, the Nobel Prize winner did what most people do when they need to understand something better.

“I read Wikipedia,” he admitted.

Luckily, he was also able to draw on his own knowledge, accumulated during a nearly six-decade career as a physicist and researcher, highlighted by the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics, awarded to Barish and colleagues Kip Thorne and Rainer Weiss for the first-ever detection of a gravitational wave. Incidentally, this discovery also represented the first observation of a collision between two black holes.

Barish, the former principal investigator of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, a partnership between Caltech and MIT that made the gravitational wave discovery in 2015, also read a number of scientific papers detailing how astronomers combined data from radio telescopes in the South Pole, France, Chile, and Hawaii to capture the iconic shot.

“It took me considerable effort that day and night to master the subject,” Barish said. “But it was worth it to provide them with a more in-depth report on this spectacular observation.”

“It’s rare to have a Nobel laureate teach a course open to both graduate and undergraduate students, and we are all thrilled to have this unique opportunity.”

– Kathryn Uhrich, dean, College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences

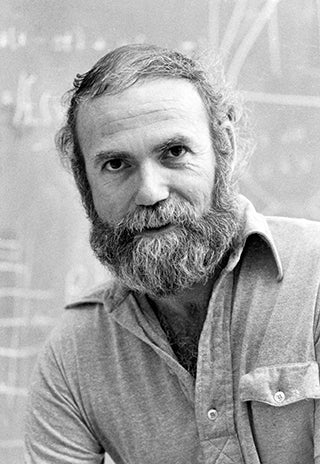

Barish at Caltech in 1979.

(Courtesy of the Caltech Archives)

A natural science

Barish began teaching at Caltech in 1963 as a postdoctoral fellow after receiving his bachelor’s degree and doctorate in physics at UC Berkeley in 1957 and 1962, respectively. He continued to teach at the Pasadena campus until he retired from the academic faculty in 2005 as the Ronald and Maxine Linde Professor of Physics.

In addition to his teaching duties, Barish served as the director of LIGO from 1997-2004, following his three-year stint as principal investigator. Barish ushered in technical changes to LIGO’s design, such as using solid-state lasers, which were more powerful than the originally planned argon gas lasers. He also expanded LIGO’s reach, establishing the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, a team of hundreds of scientists from around the world. These changes pleased the National Science Foundation, which funded LIGO at a much higher level than in previous years, and were credited with contributing greatly to LIGO’s success.

From the moment he arrived at Caltech, Barish said he eagerly taught “almost everything possible” within the physics department, from freshman and sophomore labs to a graduate course in particle physics. He made a point to mix things up rather than teach the same few classes over and over again.

“You don’t really learn a subject until you teach it,” Barish said. “My approach was to try to understand everything I didn’t understand deeply as an undergraduate by teaching it, so I moved around a lot and taught different things.”

It didn’t take Barish long to develop his own pedagogic style, one that differed from the way physics had typically been taught at Caltech and other universities, he said. While Barish’s predecessors embraced a somewhat romantic method of teaching through colorful tales of how a particular concept, law, or theory had evolved through time, the pragmatic Barish thought it best to focus on the most up-to-date principles students would need to understand the subject.

“The showmanship, the stories, and so forth, are all great,” he said. “You need to keep the students’ attention, but making sure you teach the concepts in the most understandable way is the core of my philosophy of teaching.”

When he came to UC Riverside last year, the department offered him the chance to create his own class, a prospect that appealed to him greatly. He once again decided not to focus on a specific topic, opting to provide students with an overview of the most pressing questions in physics and astrophysics that scientists are working hard to solve, including the quest to understand the origins of the early universe — and how it’s possible anything came out of the Big Bang at all.

“There’s an absolutely fundamental problem that we don’t understand, and that is why we’re here,” Barish said. “In any sort of picture we understand about the Big Bang, when all this energy was made at the beginning, as much of the anti-particles as particles should also have been made. It meant there was some asymmetry in the early universe when they didn’t exactly cancel.”

Jon Spalding, a sixth-year doctoral student in physics, took Barish’s class in spring 2019. He said the Nobel laureate’s teaching style was an effective way to learn the material.

“He just jumps to where you need to be,” Spalding said. “He’s not caught up with all these back details.”

The 36-year-old Los Angeles native also said he left the class with a renewed passion to pursue a career in physics.

“It was kind of an inspiration for me,” Spalding said. “It helps me to stay motivated to hear from the masters.”

What makes the class perhaps even more special is that it’s open to any UC Riverside student. Barish plans to teach it again next spring.

“It’s rare to have a Nobel laureate teach a course open to both graduate and undergraduate students, and we are all thrilled to have this unique opportunity,” said Kathryn Uhrich, dean of the College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, adding Barish’s enthusiasm for being back in the classroom has not gone unnoticed. “When I would see him on campus, I knew he was excited, as he always seemed to be either preparing or grading for his course.”

“I’m really looking forward to the good that this can do not just in advancing the problem at LIGO, but also how it can boost the visibility of UCR.”

– Vagelis Papalexakis, assistant professor of computer science and engineering

Forming bonds

Barish’s presence is impacting students in other ways too. When he arrived at UC Riverside in August 2018, Rutuja Gurav was preparing to graduate with a master’s degree in computer science the following spring. The 24-year-old from Mumbai, India, was fascinated by the experiments taking place at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva, where troves of valuable data were being collected. She wanted to explore ways to bring machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques to the pure sciences in an effort to better analyze that type of information and discover new insights.

Gurav’s faculty advisor, Assistant Professor Vagelis Papalexakis, suggested they speak with Barish given his background at LIGO, so the pair tracked him down following his first public lecture at UCR in April. As it turned out, Barish had long thought machine learning was being underutilized in the sciences, and he immediately suggested they meet again to speak in more detail. It wasn’t long before Barish, together with Papalexakis, convinced Gurav to forego her master’s degree and a job offer in Silicon Valley to stay at UC Riverside and pursue a doctorate.

“When a Nobel Prize winner asks you to do something, you do it,” Gurav said, laughing.

Barish introduced Gurav to the LIGO team at Caltech, and she’s now developing machine-learning algorithms to analyze the signal data produced by LIGO detectors in order to identify environmental and instrumental noise, known as glitches. Sometimes these glitches look like gravitational waves, so the more of them researchers are able to identify, the easier it will be to filter them out. Gurav published a paper on her initial findings in August with Barish listed as a co-author, and he is working closely with her during her doctoral studies.

“She’s fantastic,” Barish said of Gurav.

Papalexakis pointed to the university’s spirit of openness as key to the partnership between the physics and computer science departments, as well as the subsequent LIGO collaboration.

“The culture and the school’s collegiality is important,” Papalexakis said. “I’m really looking forward to the good that this can do not just in advancing the problem at LIGO, but also how it can boost the visibility of UCR.”

Barish also noted departments at UC Riverside are more willing to work together than at other universities.

“I actually think UCR could make a lot of impact on cross-disciplinary subjects that are harder to do elsewhere,” he said.