Rep. Mark Takano's family has fought for — and been interned by — the United States.

By Tess Eyrich

Bellevue, on the opposite shore of Lake Washington, is Seattle’s wealthier, more family-friendly sister to the east. Known for its tree-lined streets and forested trails, the “city in a park” famously hosted Microsoft’s headquarters from 1979-86. It remains a favorite stomping ground of Bill Gates, who lives just a few miles away in a waterfront mansion nicknamed “Xanadu 2.0.”

For much of Mark Takano’s family, the American experience has its roots firmly planted in Bellevue, but a much different version than the one that exists today.

Takano’s paternal grandfather arrived in Washington in 1916 after immigrating to the U.S. from Japan. A noncitizen, he wasn’t able to own land, and instead worked as a contract farmer in what was then a sleepy community of primarily Japanese American agricultural families. By 1940, he had married an American-born woman of Japanese descent and purchased several greenhouses in her name, growing both long-stemmed chrysanthemums and tomatoes he’d sell at Pike Place Market.

Within two years, however, Bellevue and the people who lived there would be forever changed by the announcement of Executive Order 9066. Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the heels of the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, the order authorized the relocation and internment of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans across the country.

Takano’s ancestors were among them; the family lost its Bellevue property. Both of Takano’s young parents, meanwhile, would live out the rest of World War II as child prisoners.

Where Citrus Once Grew

Takano’s family’s experiences figured heavily into his thesis for his Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing and writing for the performing arts, earned from UC Riverside in 2010. They’re also intertwined with his current work as the Democratic representative for California’s 41st Congressional District, a role he’s held since 2013, and as chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, which he was elected to lead in January.

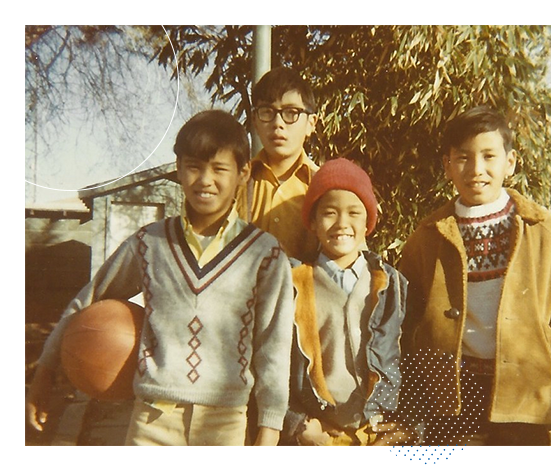

Takano’s road to the Capitol started unassumingly, in Riverside. He was born in 1960 at Parkview Community Hospital, the eldest of four sons. His father, a manager at a grocery store, was a graduate of Riverside Polytechnic High School; his mother, a homemaker who did hair on the side, had been crowned homecoming queen at Coachella Valley High School.

“As a little boy, I remember the orange groves being far more pervasive,” Takano said of his hometown. “There were a few haunts my parents used to take me to — a store called Sage’s where a chef in a big chef’s hat would carve the roast beef. Riverside was a smaller town then, but it still had elements that made it seem fancy.”

Takano knew by the time he was 13 that he loved politics. It was a combination of being raised during the heyday of 1960s progressivism and taught by young teachers — many only in their 20s — who brought guitars into their classrooms and led students in singalongs from Simon & Garfunkel’s catalog.

His interest crystallized during his sixth-grade year, which coincided with the 1973 start of the Senate Watergate hearings. He has sharp memories of long summer days spent watching the proceedings on a tiny black-and-white TV, “gavel to gavel,” he said.

“I was very impressed with Barbara Jordan, who at the time was a junior representative from Houston,” Takano added. “She gave this amazing opening speech where she spoke with such majesty and authority and eloquence that I realized, ‘I want to be like her.’ And the fact that she was an African American woman communicated to me — a little boy who had grown up in a Japanese American household — that what she represented was also possible for me.”

Often sitting behind Takano as he watched was his paternal grandfather, cigarette or pipe in hand, who had transitioned into working as a gardener since settling with his family in Riverside after World War II.

Nearly three decades earlier, from Bellevue, Takano’s grandparents and young father had boarded a train in spring 1942 and traveled to California’s Central Valley before being transferred to the Tule Lake Relocation Center. At its height, the high-security facility near the Oregon border held more than 18,000 people. Takano’s family received $400 by mail in final proceeds from their farm and never returned to Washington, he wrote in his thesis.

“As a young boy, there was an irony in me watching this great constitutional drama — Watergate — play out on TV and also coming to understand more and more how there had been a failure in political leadership to ensure the Constitution’s guarantees also applied to my grandfather,” Takano said.

In February, as a fourth-term congress-man, Takano was part of a three-person team to introduce the Korematsu-Takai Civil Liberties Protection Act, a bill that would bar Americans from being forcibly incarcerated based simply on who they are, not what they’ve done.

“We cannot allow what my parents, grandparents, and 115,000 other Japanese Americans underwent during World War II to ever happen again in our country,” he said in a statement announcing the bill’s introduction. “The cruelty and inhumanity behind the internment of Japanese Americans is a stain on the fabric of our country that was born out of hate, discrimination, and politics rooted in fearmongering.”

Teacher Becomes Student

Takano himself would remain in Riverside until college — Harvard University, which he entered in 1979 after being named valedictorian of his graduating class at La Sierra High School. He earned a bachelor’s degree in government, and, perhaps inspired by his own experiences in school, returned to Riverside to teach middle and high schoolers in the Rialto Unified School District.

While a teacher, he made his first foray into local politics with his election to the board of trustees for the Riverside Community College District in 1990.

Fresh off the momentum of that initial win, Takano ran for a congressional seat in 1992 and lost by only 500 votes. Just two years later, he was outed as gay during his second congressional race, and again lost the seat. Yet rather than succumb to defeat, Takano pressed on, pushing for reelection to the community college board — and this time, succeeding. Within two decades, he would become the first openly gay person of color in Congress.

But before that could happen, Takano continued to teach — all told, he spent 24 years in the profession — and in the late 2000s, he began looking into master’s degrees.

“I wanted a credential that would deepen my ability to teach what I was teaching, which was high school and mainly language arts, and also allow me to potentially branch out to the college or university level,” Takano said.

He chose UCR’s MFA program, and although he said it could sometimes be jarring to take part in the program’s workshops after not being a student for so long, the experience allowed him to examine his family history in greater depth. Along the way, he was inspired by the work of Annie Proulx, author of the short story “Brokeback Mountain.”

“That story left a mark on me in terms of teaching me about the power of place and the power of time, and how people’s choices are often limited by the place and time in which they’re situated,” Takano said. “I began to think about how time and place have impacted me, and how they must have impacted my grandfather. Each generation has its own set of choices and possibilities.

“One of the big facets of American life is that we come here — most of us are immigrants at some point — and there’s an enormous part of our culture that drives us forward,” he added. “We tend to focus so much on the idea of opportunity, and that makes us grab for the future, but as a result, we lose connection with where we come from. I believe in so much of what this country is about, but I do think we have a tendency to disconnect with our history.”

For Takano, efforts to reconnect with his own heritage had been ongoing. A significant chunk of his 130-page, memoir-like thesis details his 2002 trip to Japan with his father’s cousin Kikue Takagi, who had survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima as a child.

The visit was a sobering one for Takano, then 40, who said it gave him a new understanding of how self-conscious his family members in the U.S. had been about “trying to prove their American-ness.” Touring the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, meanwhile, had its own effects.

“It didn’t make me a pacifist, but it’s shaped my politics in a way that makes me very skeptical of executive authority and the ways it gets manipulated, and of the potentially manipulating authority of politics in terms of steering us into unnecessary wars and conflicts,” Takano said.

“I believe every world leader should be required to visit Hiroshima before they take office. They should have to walk the grounds. Having and deploying nuclear weapons is an enormous responsibility; my concern is with how we sensitize political leaders to the decisions they’re going to make.”

Getting to the Point

Looking back at his own transition to political leadership, Takano said the MFA course that benefited his future career the most was a surprising one: a workshop on writing books for children. The course was taught by Juan Felipe Herrera, UCR professor emeritus of creative writing, who was named U.S. poet laureate in 2015.

Takano said the workshop — in which students were tasked with telling a story in just 16 pages — taught him the importance of conciseness in his communication, especially on the national stage.

“We use the word ‘narrative’ a lot in politics — how do you reduce a story to just a few words?” he said. “There tends to be a lot of resentment when people take up too much time in Congress. You’ve got to get to the point.”

It’s a lesson Takano learned well after being elected, at long last, to the U.S. House of Representatives in fall 2012. His 41st District includes Riverside, Moreno Valley, Jurupa Valley, and Perris.

Despite shifting from teacher to legislator, Takano remains focused on education as a member of the House Committee on Education and Labor. The House Committee on Veterans Affairs, of which he has been a member since 2013 and now serves as chair, oversees the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, veterans’ hospitals and medical care, and veterans’ cemeteries such as Riverside National Cemetery, now one of the largest in the system of 136.

For Takano, veterans’ issues are personal ones. He is well versed in Riverside’s military history, referencing both March Field, created during World War I and now known as March Air Reserve Base, and the World War II-era army facility Camp Anza. It’s a history that extends into the present, Takano said: Riverside County, with its historically high levels of military participation, is now home to the country’s eighth-largest veteran population.

“My interest in veterans is even more directly connected to my uncles, who fought for our country,” Takano added, noting that three of his great uncles fought in World War II as part of the Army’s 442nd Infantry Regiment, a highly decorated unit composed of mainly Japanese American soldiers.

“I’m very aware that their decision to fight for our country, in what was the most decorated fighting unit of its size, allowed me to become a congressman today,” Takano said. “I had another uncle who fought in Vietnam, and he committed suicide when I was 10. I never thought of my family as a military family, but in fact, every generation of my family had military service members.”

A day before the first of two interviews for this profile, the U.S. Senate passed the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act, which extends disability benefits to offshore Vietnam War personnel — namely sailors — who claim they were exposed to the chemical herbicide Agent Orange. President Donald Trump signed the bill, for which Takano was the lead sponsor, into law on June 25.

“Before this bill, you had to actually show that you were on land to receive disability benefits,” Takano said. “It’s been a decades-long struggle.”

Though that particular struggle might be over, it’s far from the only one that occupies Takano’s conscience. Also on his mind are the thousands of veterans who were previously exposed to radiation and haven’t been compensated or received disability benefits, as well as the next generation of young service members.

“Part of my concern comes from being a teacher and watching the number of my students who joined the military,” Takano said. “For a lot of kids, the military and the GI Bill represented ways they could broaden their horizons.

“I’m very attentive to the ways in which predatory institutions can go after people, and I feel a very strong need to be protective of veterans, but also of low-income families,” he added. “That’s where my political power is best used.”